South Korea’s Population Crisis: A Fertility Rate That Money Cannot Solve

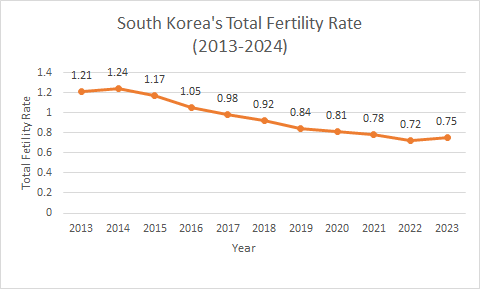

South Korea’s population crisis has reached an unprecedented level. The total fertility rate was 0.72 in 2024. As of February 2025, it stands at 0.83. South Korea faces the world’s most severe population crisis. These figures have never been seen before in human history. Why is this happening in an economically advanced nation?

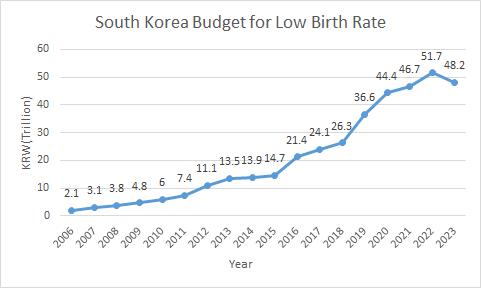

Most people connect this problem to money. Many media outlets say young generations aren’t having children. They blame soaring prices, housing costs, and unbearable private education expenses. The Korean government has poured astronomical amounts into birth promotion policies. This has continued over the past few decades. However, most policies have not been effective for actual users. South Korea’s population crisis continues to worsen even now.

This phenomenon suggests the problem isn’t simply about money. At this point, I ask a different question. Korea has an internationally high income level. Despite extensive support, the birth rate does not rise. Isn’t “money” not the answer? If so, we need to look into the thoughts of the generation that should be having children. We must understand why they refuse marriage and childbirth. I believe this birth rate problem should be analyzed from a cultural perspective. We must examine the culture in which they grew up.

Cultural Factors Behind South Korea’s Declining Birth Rate

Marriage and childbirth were once a natural life process. Society encouraged everyone to embrace this path. It was seen as an attractive life choice. However, this is no longer appealing to the younger generation. Why? The answer lies in their childhood years. Their values were formed during specific social and cultural phenomena. These shaped the current generation that should be having children.

1. Korea’s Baby Boom Generation and Their Children

Korea’s current childbearing age group was born in the late 1980s to early-mid 1990s. They were born during a period of national prosperity. This was the “Three Lows Boom” from 1986 to 1989. Their parents were most actively engaged in economic activities during this time. They spent their childhood in affluence. The 1997 IMF Asian financial crisis occurred. However, Korea successfully overcame it and grew well. This generation grew up experiencing Korea’s remarkable growth.

They grew up under a specific slogan. It said “Don’t discriminate between sons and daughters, have only two and raise them well.” Most were only children or had just one sibling. They grew up in an affluent environment that valued individual characteristics. Therefore, they developed different traits than previous generations. They focused more on personal life.

2. South Korea’s SNS Generation and Declining Fertility

Before Facebook opened the era of SNS globally, Korea had “Cyworld.” It launched in 2003. It wasn’t a worldwide hit. However, the majority of Korean teenagers used it from 2004 to 2009. The generation currently experiencing declining birth rates already grew up with SNS. This happened during their formative years when their values were being shaped.

Some demographers analyze that SNS increases “psychological population density.” They believe it’s related to low birth rates. Through SNS, people indirectly experience countless others’ lives. The sense of deprivation and competitive psychology grows. They feel they are falling behind. The generation that experienced SNS the fastest in the world is now recording the lowest birth rate. This may not be a coincidence.

Facebook became widespread in 2014. Based on this timing, Korea may be showing a “prototype.” It could be the SNS-driven low birth rate problem that humanity will face. Korea is 10 years ahead.

3. The Harm of Legacy Media

All Koreans of current childbearing age grew up watching negative portrayals. They unconsciously absorbed negative messages about marriage and childbirth. Their parents’ generation used specific words for people who didn’t marry. Terms like “old maid” and “old bachelor” were common. However, such direct and aggressive words are no longer used.

Instead, they have been replaced with supposedly hip new terms. These include “gold miss,” “unmarried tribe,” and “DINK (Double Income No Kids).” These terms have been continuously exposed through media.

Dramas and variety shows on public broadcasting repeatedly conveyed a message. They said “you’ll suffer if you get married and have kids.” They either showed fantasies far removed from reality. Or they invited people with extreme marital lives. They highlighted only the hardships of married life. They also showed celebrities’ luxurious married lives. This made ordinary people feel the wealth gap and sense of deprivation.All Koreans of current childbearing age can be said to have grown up unconsciously watching negative advertisements for the “product” of marriage and childbirth. Their parents’ generation used to use words like “old maid” and “old bachelor” for people who didn’t marry. However, such direct and aggressive words are no longer used. Instead, they have been replaced with supposedly hip new terms like “Gold miss,” “unmarried族 (tribe),” and “DINK (Double Income No Kids),” and these terms have been continuously exposed through media.

Additionally, dramas and variety shows on public broadcasting repeatedly conveyed the message that “you’ll suffer if you get married and have kids.” They either showed fantasies far removed from reality or invited people with extreme marital lives to highlight only the hardships of married life. They also showed celebrities’ luxurious married lives, making ordinary people feel the wealth gap and sense of deprivation. As these messages were repeated, one powerful slogan was engraved in the unconscious minds of Koreans: “It’s better not to marry, and even if you do marry, it’s better not to have children.”

The Cause of Policy Failure: Failure to Understand Consumer Values

The government perceived this problem only as a “price” issue. They judged that the product of “marriage and childbirth” is expensive. They thought people would buy it if they reduced the price. Accordingly, they spent hundreds of trillions of won. They provided subsidies, supported housing, and improved various systems.

However, this approach missed the essence. The problem is not money. The appeal of the “product” itself has disappeared. Consumers already perceive the social costs and sacrifices of marriage and childbirth. They see these as far greater than the happiness and satisfaction the product provides. This perception is extremely powerful. It can never be changed with hundreds of trillions of won in subsidies or policies.

The government and society failed to grasp something crucial. They didn’t understand why this product is not attractive. They didn’t discover what values consumers truly want. Ultimately, South Korea’s population crisis is not one of “price” but of “value.” Marriage and childbirth are like a product I wouldn’t buy even with money in my hand. They have already lost their social value.

Solving South Korea’s Population Crisis: New Strategies Needed

Now we must approach this in a new way. The existing approach was financial support. It was like “discounts” on the product. Now we need marketing that reestablishes “value.”

We shouldn’t simply say “we’ll make the cost of having children cheaper.” Instead, we must sincerely communicate something different. What positive values does raising children bring to individuals and society? We must show that marriage and childbirth are not difficult sacrifices. They are experiences that enrich each individual’s life.

In this process, the media clearly has responsibility. Media has a specific characteristic. Negative stories are consumed and spread more than positive stories. They have produced negative content about marriage and childbirth for higher ratings. If they continue to produce content like the current ones, the situation will be far from improving. They chase only ratings.

This problem cannot be solved by government financial support policies alone. The entire society must rediscover something important. They must find the value of marriage and childbirth. They must begin new “marketing.” This marketing should sincerely talk about its positive aspects.